A Wildfire Story: Dinner

/Last year was a big one for forest fires in western North America. One striking visualization by NASA shows a near-constant plume of smoke billowing out from British Columbia, Alberta, and the western United States. Last year, British Columbia experienced the worst forest fire year since record-keeping began in 1950, with nearly 900,000 hectares (9,000 km²) burned.

How do forests survive these catastrophic events? How do they bounce back, so successfully as to be termed “fire-driven” across much of western North America? The answer lies in adaptation.

NASA visualization of sea salt, smoke, and dust traveling on air currents in 2017. Image taken from video by NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center.

Some like it hot

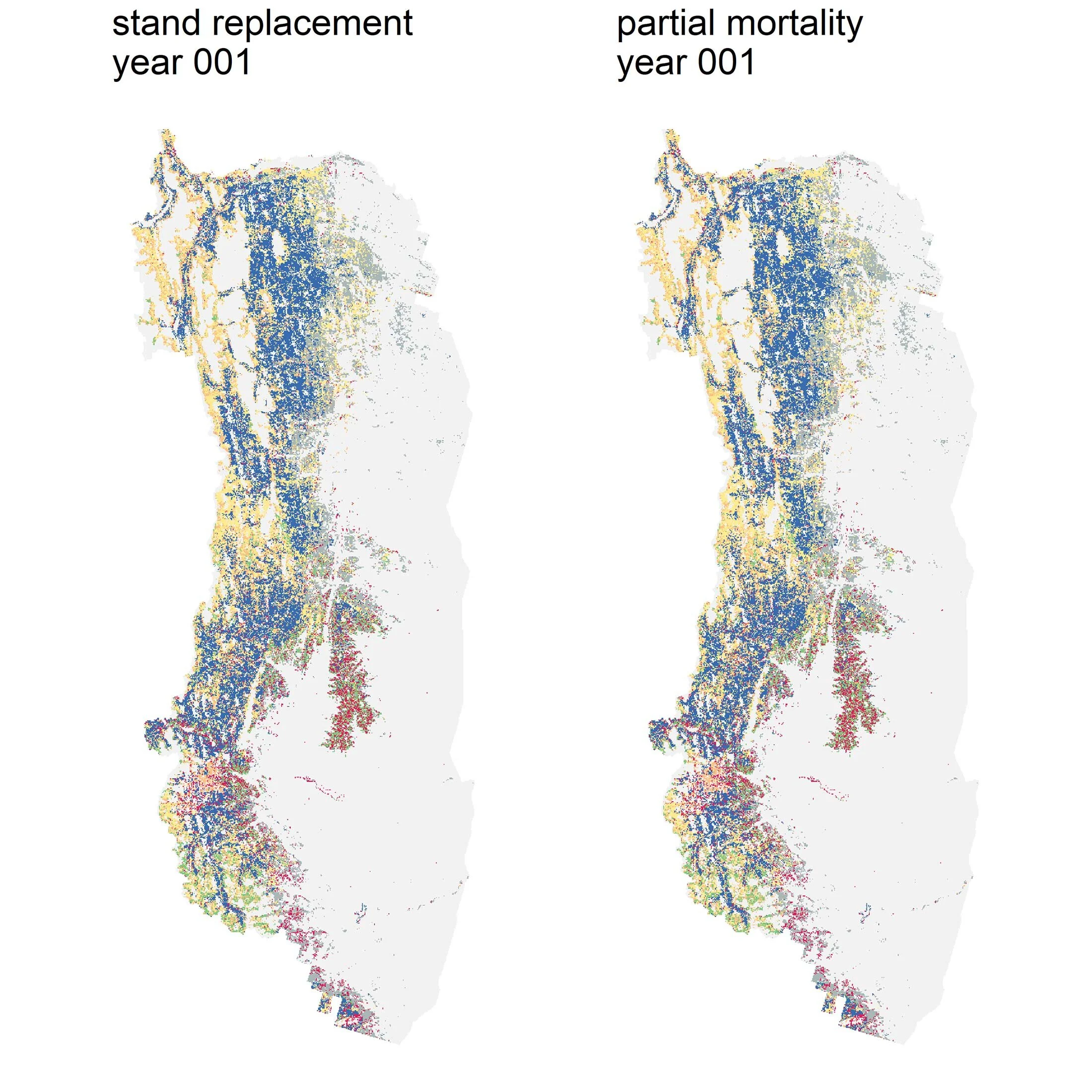

Depending how intensely a forest burns, there are tree species that have evolved to withstand the heat, and others that have invested in seeds that will sprout after a fire (see A Wildfire Story: Severity).

But there are even more species that rely on these burned habitats, and some of them are so closely tied to burned forests that they are icons for them. The Black-backed Woodpecker is one of these iconic species.

A Beetle Buffet

Why is the Black-backed Woodpecker attracted to burned forests? The answer, like with so many of us (myself included), is simple: they like to be where the food is. There are entire communities of insects, especially beetles, that specialize on trees that have been killed or wounded by a fire.

Bark beetles and wood-boring beetles are the main among the insects that appear shortly after a fire. One striking example is Melanophila acuminata (“Black Fire Beetle”), a wood-boring beetle which is known to show up at forests while the trees are still smouldering—members of these genus are actually able to detect infrared radiation emanating from hot objects from hundreds of kilometers away. Similarly, many bark beetles are among the first to arrive because of their ability to detect heat and smoke. Bark beetles are such early arrivals, in fact, that other species home in on the scent of bark beetle pheromones to locate burned stands.

Black Fire Beetle (photo by AG Prof. Schmitz).

White-spotted Sawyer, oregonensis subspecies (photo by Thomas Schoch).

When beetles arrive at a burned stand, they set to work chewing their way into trees which are dead or badly damaged, and lack the usual defenses (e.g., fast-flowing pitch to flush them out from wounds in the bark). Some, like the White-spotted Sawyer (a type of long-horned beetle), simply lay their eggs in little cavities they chew into the bark. Small bark beetles, in contrast, burrow under the bark and lay their eggs in “galleries”, which can be seen on fallen logs or dead trees where the bark has fallen off. When the eggs hatch, larvae slowly chew their way through the soft, nutritious layer between the tree’s bark and the hard wood that makes up the main part of the tree. Deeper forays are made by wood-boring beetles which, as their name implies, have larvae which make their way into a tree’s sapwood.

When a forest has been infested by beetles after a fire, sometimes their chewing is so loud (particularly the wood-borers), they are audible to people. And to a woodpecker, it sounds like a dinner bell.

The early bird

These beetle-infested trees represent a buffet for birds, so long as they can get to them. This is where woodpeckers come in.

Many species of woodpeckers rely on old, decaying trees found in forests that have been undisturbed for a century or more. But others, like the Black-backed Woodpecker, prefer recently burned forests. Their characteristic tapping is a common sound in a burned forest, as they work their way around trees and extract beetle larvae from under the bark. While many woodpeckers are commonly found in older forests where dead trees are infested with beetles, the Black-backed Woodpecker’s preference for burned forests is clear across much of its range.

Male Black-backed Woodpecker (photo by US Fish and Wildlife Service).

Female Black-backed Woodpecker (photo by Francesco Veronesi).

And the woodpecker has many adaptations which make it well-suited to forage for beetles under challenging conditions. Its namesake black plumage makes it hard to spot against—you guessed it—a charred tree. It is also able to drum into trees with higher force than other woodpeckers, allowing it to peck through hard bark and extract the beetles underneath. Like all woodpeckers, it has a strong skull which is adapted to be slammed against trees without causing brain damage.

In fact, Black-backed Woodpeckers rely so heavily on burned forests, groups in the United States have petitioned for them to be listed under the Endangered Species Act because of fire suppression and declining populations. If Smokey the Bear is the mascot of the anti-wildfire movement, the Black-backed Woodpecker is his counterpart on the other side of the debate.

Fire Cycle, Life Cycle

Forests were hit really hard by fire in 2017, and while the immediate aftermath may feel Mordor-esque, they will likely be humming with life within a few years—or creaking with wood-borers, as the case may be. Fire-loving beetles and Black-backed Woodpeckers are just one small part of the many plants, insects, wildlife, and other organisms that thrive on habitats that have been burned. They are a part of the legacy that wildfires leave on a landscape.