Meet the Team: John Stadt

/Landscapes in Motion is an ambitious project that has deep roots in research around fire history and its effects on ecosystems in Alberta. In 2015, researchers at the Government of Alberta's Forest Management Branch identified mixed-severity fire regimes as a research priority and set events in motion that led to the Landscapes in Motion project as it is today.

We interviewed John Stadt, the Provincial Forest Ecologist with the Government of Alberta and the Science-Policy Advisor for Landscapes in Motion. Our goal was to learn more about why the Government of Alberta feels this project is important and what they hope to learn from it.

Where are you from? What is your background?

I grew up in Victoria and fell in love with the diverse forests of southern Vancouver Island. Sunday afternoon family walks would be through Garry Oak Arbutus woodlands while summer camping trips saw our family exploring coastal western red cedar forests on the west side of the island or the drier Douglas-fir stands on the east side. I think I realized from a young age that I wanted to contribute to the good stewardship of these forests. I started my university studies at the King’s University, which is what first brought me to Edmonton, Alberta. Stewardship was an important theme in the liberal arts program there. I finished my Bachelor of Science in Botany at the University of Victoria where highlights included making plant collections from the mountains of central Vancouver Island, and completing an honours project on the shore-pine variety of lodgepole pine. I returned to Edmonton for a Master of Science at the University of Alberta where I studied how lodgepole pine forests in the Canadian Rockies change through time—this is where my love for Alberta’s forests really began. After university I worked as a research biologist for the Canadian Forest Service in Edmonton and then as a forest ecologist for BC Environment in Burns Lake in northern BC.

What do you do?

I’ve worked for the Government of Alberta for 15 years as the Provincial Forest Ecologist.

My department, Alberta Agriculture and Forestry, is the steward of Alberta’s forests. Our job is to ensure that they are managed sustainably—that they maintain their ecological integrity so that they can continue to provide for Albertan’s values. So my job is to provide the scientific basis for this. I translate the science to our forest managers, and I take the tough questions they face and turn them into science questions for the research community to address. To do this I depend on partnerships and collaborations with researchers across Canada and elsewhere.

When you get out into the field, what part of the field work are you most excited to participate in?

I love walking through a forest stand with other researchers who have learned to see details and patterns that I had not seen before. Seeing fire scars and where they are placed… seeing the presence or absence of downed wood and the implications on past fire… These all tell a story about ecological processes and human activities in that forest stand.

Another highlight of getting into the field is working with the students who conduct data collection and field sampling because of their enthusiasm and willingness to ask questions about everything.

Being in the field is so important. It helps me stay curious so I continue to ask the important questions.

Was there a specific event or situation that piqued your interest in mixed-severity fire regimes?

In forest management we are often focused on the rate of harvest disturbance to ensure that we leave the right balance of old, mature and young forest, and on the pattern of harvest disturbance to prevent fragmentation of forest habitats. We study forest fire regimes to inform these decisions. But these studies have shown us that the question is not just about the rate and pattern of disturbance, it is also about the intensity or severity of disturbance.

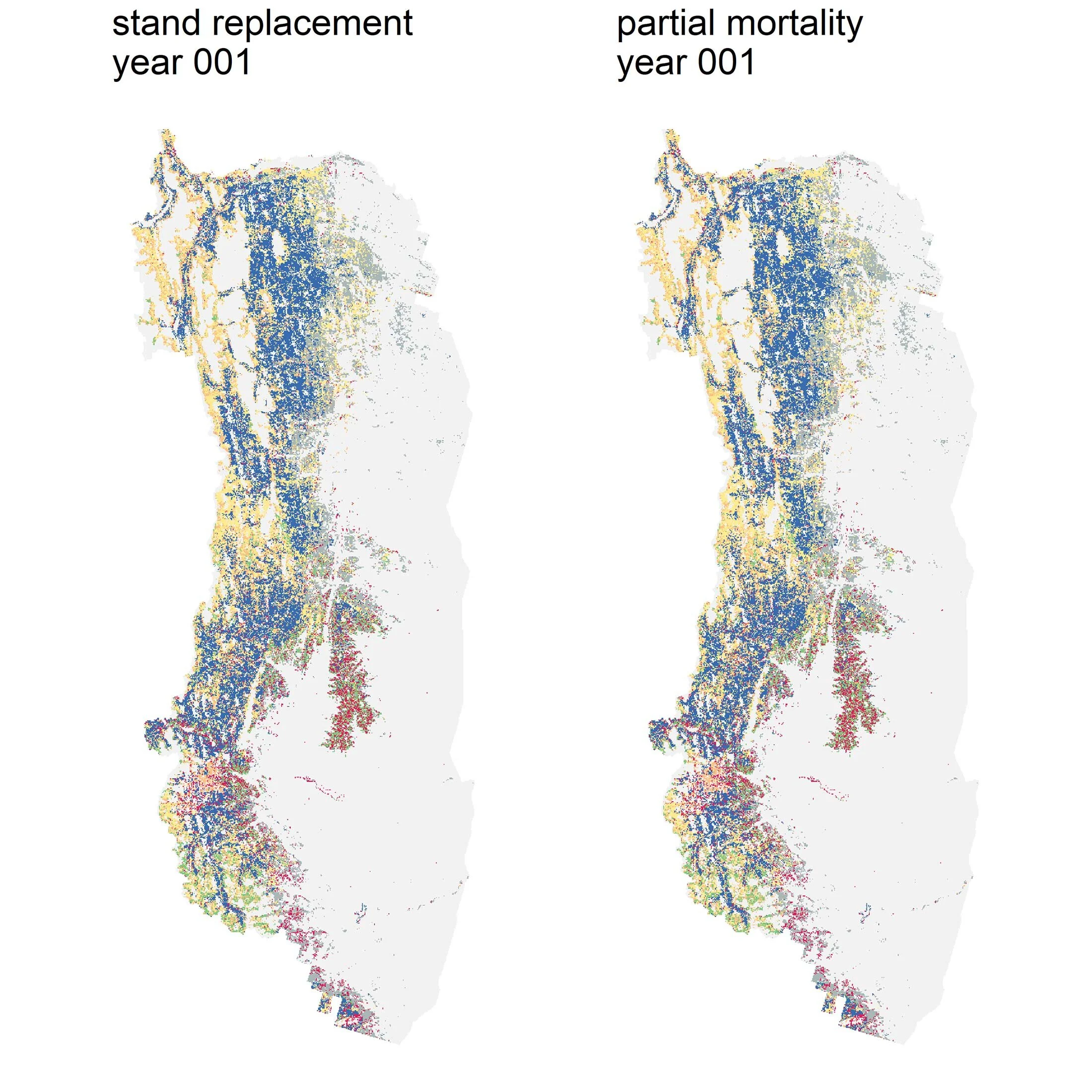

Fires are not just stand-replacing. While some fires kill most or all of the trees in a stand, prompting the growth of young trees that are all the same age, many do not. Low intensity fires don’t kill all the trees and they leave much more complex patterns after disturbance. If we want to be informed by fire regimes in our management, we had better make sure that we are not trying to imitate fires based on an over-simplified understanding of what they really do. It’s been well understood for a while that these mixed-severity fire regimes occur in forests in other areas of western north America such as in Ponderosa Pine and Douglas fir forests. However, to start seeing evidence that this kind of regime may exist in Alberta too, where we have always implicitly assumed a stand-replacing regime, was very eye opening for me. It makes me realize that we always need to question our assumptions and test them.

What is your role with Landscapes in Motion?

The idea for this study began with questions we had been asking about how to be good stewards of the forests in southwestern Alberta. My role is to work with the different research teams to make sure that these questions don’t get forgotten as this study evolves and grows. My role is also to translate the results of this study to forest planners and forest managers to enable them to make good decisions.

What questions do you hope will be answered by the project?

Do we have a mixed-severity fire regime in southwest Alberta? If so, how extensive is this regime across this region? What patterns does this regime create at the stand and landscape scale in our forests? How do we use this knowledge to inform forest management planning so that forest landscapes shaped by harvesting continue to provide for biodiversity and the ecosystem services provided by these forests? Forest harvesting, when informed by science from projects like this, can contribute to creating forest landscapes that are resilient and diverse.

How do you think this project will benefit Albertans?

This project will test our assumptions about the natural patterns of forests at the stand and landscape scale. Forests change slowly and human memory is often short. The forest patterns we see today have been affected by past human actions such as settlement and fire suppression. By letting the landscape tell us what is natural, it will allow us to better manage these forests to maintain ecological integrity. Forests with ecological integrity and which have the full range of natural patterns are more resilient to many stressors and are better able to continue to provide for the wide range of values Albertans have.

What excites you most about this project?

The project is like detective work—looking for clues. Fire regimes occur over centuries and we cannot go back in time to study the regime directly. So this project needs to look for all the different pieces of evidence left behind that tell a story of what is going on. An exciting part of this study is that we are not just using one line of evidence. For example, one part of the project looks at fire scars on trees—did trees survive multiple fire events? Another part of the project looks at the incredible photo archive provided by the Mountain Legacy Project to look for evidence of the patterns of disturbance on the landscape a century ago. These and other clues give us a more complete picture of how fires have shaped our forests. And this will help us in our decisions on what these forests should look like in the future.

What is the most interesting or exciting thing you've discovered about forests during your career as a scientist?

That each forest stand tells a story—a story about all the things that made it what it is today—local climate, soils, hydrology, past fires. This story also includes all the different ways humans have shaped it, from Indigenous burning to historical and modern tree harvesting. How this story will continue in the future with realities such as climate change and increasing human impacts makes understanding this past story so important.